A World I Never Made

Click for more information on

William Downs

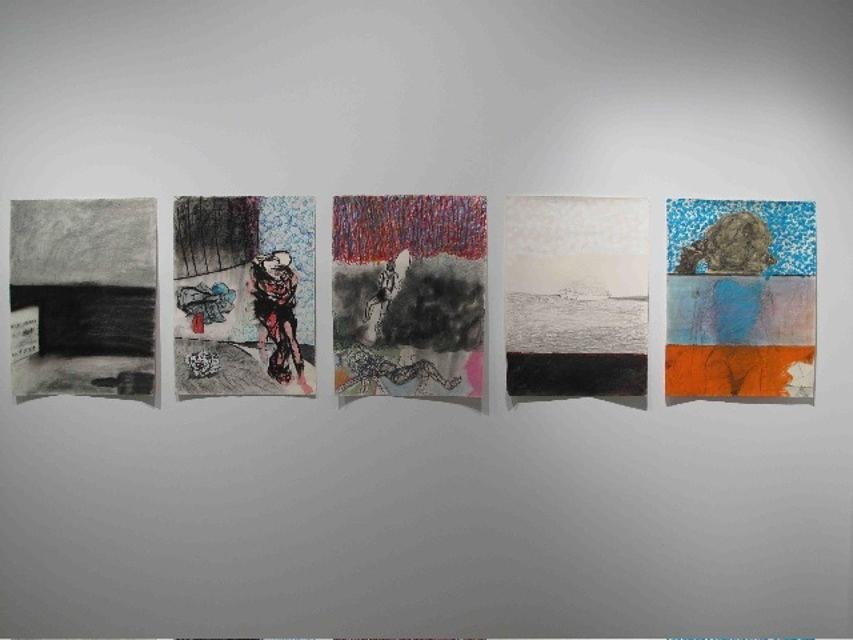

“A World I Never Made”

By Lyra Kilston

William Downs collects old chronographs—watches with a stopwatch function that tell time in three ways simultaneously. His collection of handcrafted timepieces, found at flea markets and thrift stores, links to a sturdier, slower past. While his chronographs play no direct role in his artwork, the impulses that draw him to them—the passage of time, the attempt to measure it objectively, and the desire to preserve what is fading into obsolescence—appear vividly in his loose, hallucinatory drawings. Downs talks about his artistic practice in terms of varying “tempos.” He slows down to capture detail and accuracy, and then draws quickly as though to mirror the speed with which impressions pass through his mind. He often employs found paper, like phone book pages, file folders, or napkins, so the papers’ past lives remain visible. For the same reason, he welcomes the charcoal smudges of his own hands and the traces of erasure that blur through his drawings.

In several of Downs’s new drawings, a rollercoaster’s curves, knots and vertiginous rises appear as an archaic monument to the time of its heyday. In one drawing, its herringboned scaffolding peaks over a mass of sky blue and black scribbles. Elsewhere it appears above a smear of black from which a small, penciled city emerges. In a third drawing, the vague allusion to its swooping tracks makes up the foreground of an empty landscape, over which flares an impossibly enormous blue and magenta hurricane. Other loaded motifs appear repeatedly in these drawings—lone airplanes, scatterings of birds, vaguely sketched men and women, and more furious hurricanes rendered in thick, dark Vs.

Downs draws every day and everywhere, and he never throws any drawing away. His work acts as an exhaustive, if coded, record of his life, and each drawing he unearths conjures the precise place, time, and frame of mind he was in when he made it. For the past few years, Downs has commuted back and forth to Baltimore once a week by train to teach, and he spends the time drawing—the landscape flitting by like thoughts.

He first studied painting and printmaking, and his early work reveals an expressionistic style and intense color. But several years ago, color began to feel too easy a seduction and Downs pared his grammar down to black charcoal, watercolor, or pencil on paper for awhile, looking at Japanese ink drawings in which the slightest gesture evoked a form. Throughout the years, figuration has remained constant, but in these new drawings the scribbled, sometimes colorful flurries that creep down from the sky or rise from the ground invoke the a vast, irrational realm of feeling that so often impinges on attempts at logical narrative.

It is the subconscious mind, with its opaque, corroded channels, which Downs hopes to access. Rummaging through fragments of dreams, transitory images, memories, or imagined scenarios, he seeks out a direct transmission from mind to paper, mentioning the Surrealist practice of Automatic Writing as an influence. The result is a feral, yet disciplined body of imagery in which the artist’s subconscious is glimpsed in enigmatic arrangements. He often draws what he calls the “double-double,” in which a single person’s face is sketched several times on one body, looking around in different directions. The doubling also appears in older sketches of Siamese twins, three-headed boys, or women with twisting torsos and multiple breasts. Besides hinting again at the passage of time and movement, the many-faced figures imply a multiplicity of personas, another way in which Downs pursues the daunting task of rendering feeling.

In his search for spontaneity, purity of fleeting impression, and devotion to a daily practice, Downs’s approach is similar to that of Frank O’Hara’s in his series of Lunch Poems. As O’Hara wrote: I am naked as a table cloth, my nerves humming. It’s a line that describes both artists, as their work strives to receive a parade of impressions, to be a blank canvas upon which the mercurial world spills. Yet where O’Hara celebrated the banal and jangling poetry of New York at noon, Downs’s imagery is fevered, invented and psychological—bodies warp, a huge shark looms, figures walk toward a frizzled graphite hurricane. In his Brooklyn studio, Downs pulls out a favorite work, a small found piece of paper with a coffee spill on it. The pale brown wash formed a serendipitous Rorsach blot that Downs intuitively riffed on, integrating it into a drawing of a man. He commented later, “I’m always looking at the sky. It’s a really nice place to find drawings.”