"SOFT POWER" PRESENTED BY BONISSON ART CENTER

Click for more information on Naomi Safran-Hon

Bonisson Art Center is pleased to present Soft Power, a solo show with paintings by Naomi Safran-Hon.

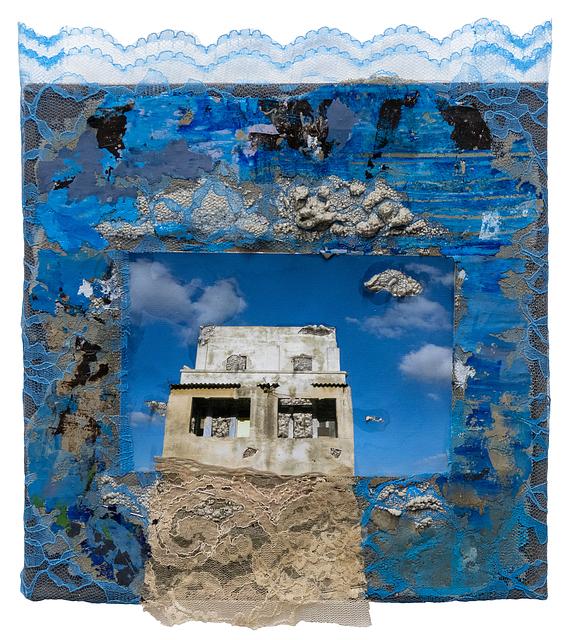

In Soft Power, Naomi Safran-Hon’s works, as with previous shows, are described as paintings. But is it enough to call them just that? Each work is a synthesis of photography, drawing, sculpture, and painting brought together through perspectives that are both historical and fictive. Her work is a fusion, a coalescence of disparate materials — lace, cement, photographic prints, pigment, acrylic paint, gouache, and sundry manufactured objects such as PVC piping — that requires discussion of her process in order to understand how she brings into concert materials, methods, and viewpoints that otherwise seem mutually incompatible.

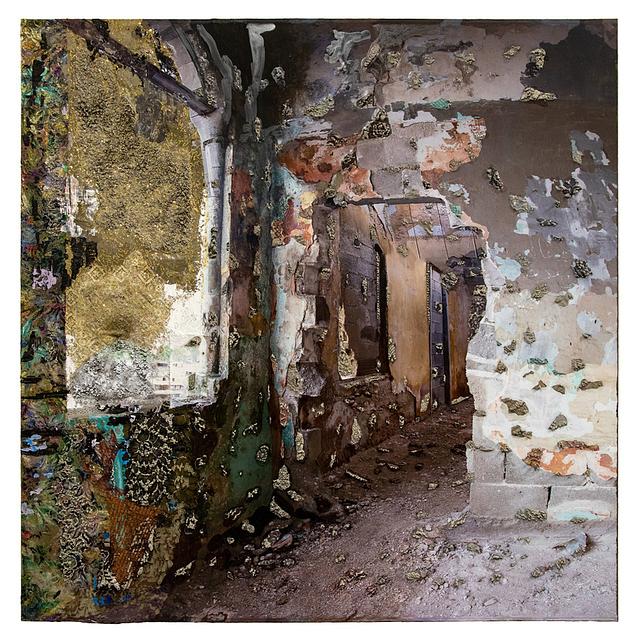

This process entails Safran-Hon taking the photograph she means to work from, mounting it on canvas, then painting on it and cutting holes in it. The hole-cutting is crucial. In the case of the works that document the homes which Palestinians were driven from or abandoned in her hometown of Haifa in Israel, she forces cement through the back of the canvas, through the pre-made openings so that when the cement erupts through the image’s surface and sets in stony stalactites the work becomes a document of devastation. But each piece is more than that too. As the viewer can see in the piece “Looking Back, Building Anew” to the left of the composition Safran-Hon opposes the destruction with vibrantly polychromatic abstract patterns interwoven with lace. The artist means to aesthetically intervene in an historical moment that actually can’t be rescued. Nevertheless, she intends to rescue it, save it from merely becoming a meme or tabloid headline, or an image that reads in the lexicon of our global popular culture as spectacular violence and correlated suffering.

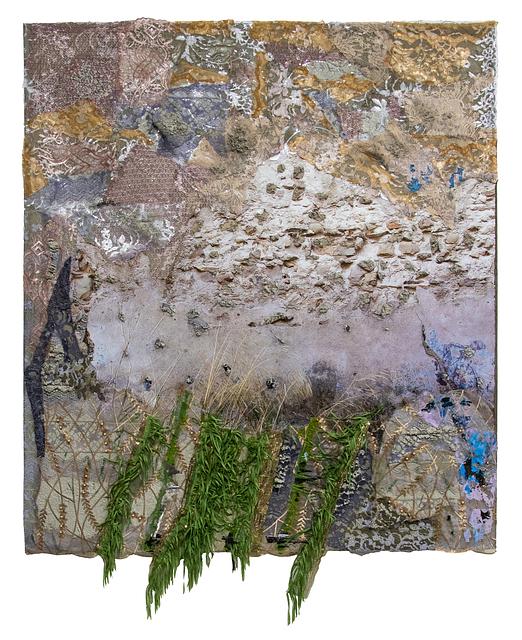

In other pieces, such as “If the Walls Could Talk They Would Say Her Name” the artist makes a more straightforward idyllic image. But it’s complex because of its disparate aspects: It might represent a beach with the spare sections of light sand in the lower third, with a clump of beach grass appliqued to the canvas, hanging off its edges, venturing off the pictorial plane and into the viewer’s reality. In the upper third however, rocky outcroppings develop into subtly colored bits of patterned lace that become a kind of variegated firmament, somewhere above the earthly experience of a seashore, suggesting an aesthetic empyrean of Safran-Hon’s own making.

Over time Safran-Hon has made it her work to bring opposing histories, concerns, materials together aesthetically to bridge that imagined gap between the beautiful and degraded, everyday objects. Her use of lace, a fabric that has quintessential feminine associations, is instrumental in providing a base for the decorative patterns she renders in her canvases. Crucially, it also supports the cement, which without this substrate would crumble into dust. We might think of the cement as unpliable, as resistant, as typically masculine, but it only becomes unyielding with the reinforcement of the underlying (feminine) lace.

The artist also melds the fictive and the historical, moving between documentary image and aesthetic embellishment, negotiating a balance between the coercive force of our histories and the insular, sometimes apolitical arena of artistic production. On one hand, Safran-Hon could choose to disregard where she comes from, ignore the plight of those harmed and immiserated by the Israeli government, by making paintings that subtly argue for escapist aesthetics. On the other hand, (and too many artists do this) she could devise images that are so loyal to the history she was born into that the work can’t offer any other way of being. Instead, Safran-Hon diffuses through these visual chronicles of what happened glimpses of what may yet come to be.

What’s more, Safran-Hon also brings together collective and personal narratives. Each image here is a view of how she sees and has experienced her social reality. But each image also conveys a perspective on how her viewers might regard our own: We are almost daily challenged by encounters with those who are ostensibly our gender, sexual, ethnic, or socio-economic opposites. We imagine that we must contend with them in order to survive. Nevertheless, as the interdependence of cement and lace in Safran-Hon’s paintings suggests to us, we are vulnerable. We too can break or be torn apart, and then, only with the support of others will we have the chance to reconstitute ourselves.

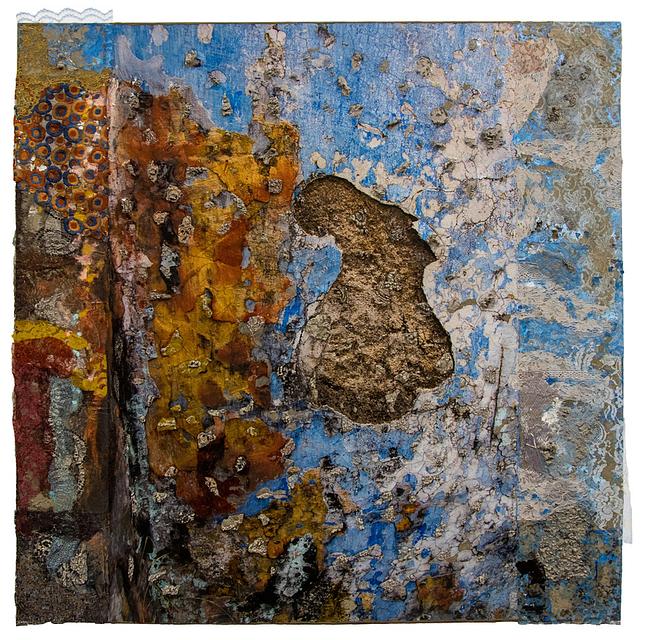

There is yet another way in which Naomi Safran-Hon brings together antithetical perspectives by serious yet playful means. Soft Power demonstrates her growing interest in abstraction, edging away from figuration to probe what emotional, aesthetic, and conceptual meanings might be conveyed through her process. Ultimately, Naomi Safran-Hon does not just make paintings, but expanding on and pushing against our inherited notions of what painting should do or be, her work constitutes propositions to see our culture as a place of intersection, of interdependence rather than only of conflict and contest. She proposes that our encounters with the structures around us and the people who inhabit them, in all their contradictions and ironies, those encounters might still be laced with loveliness.